| Hint | Food | 맛과향 | Diet | Health | 불량지식 | 자연과학 | My Book | 유튜브 | Frims | 원 료 | 제 품 | Update | Site |

|

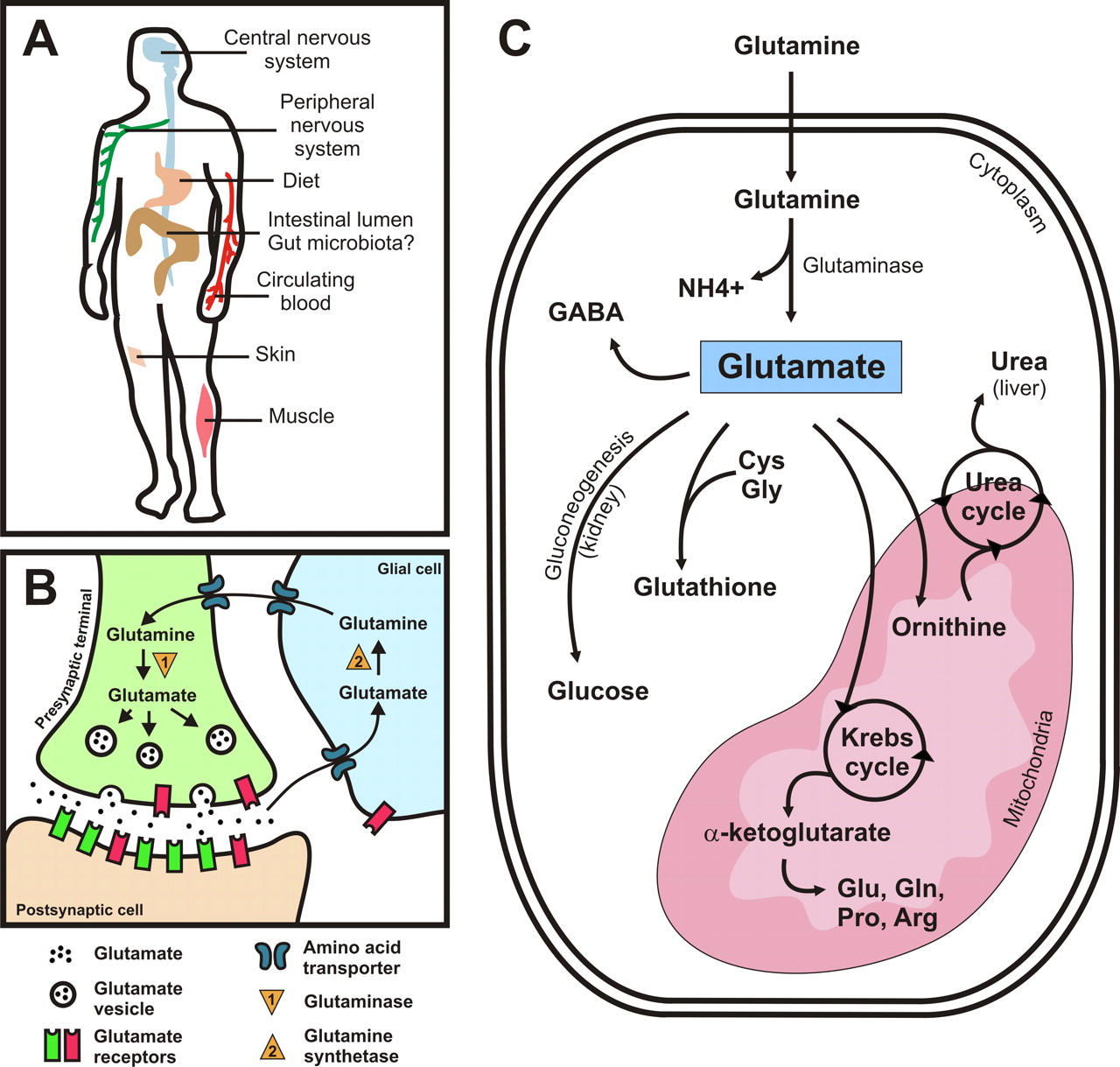

MSG ≫ 정미료, 역할, 논란 Glutamic acid : mucosa cell의 에너지원 글루탐산 역할 - 점막세포의 에너지원 - 뇌의 에너지원 - 혈액-뇌 장벽(BBB : blood-brain barrier) 글루탐산은 장건강에 중요하다. 우리가 음식을 먹으면 단백질을 구성했던 글루탐산이던 MSG로 추가한 글루탐산이던 모두 분해되어 아미노산의 형태로 흡수된다. 그런데 이 글루탐산을 1차적으로 흡수하는 소장의 상피세포는 아주 독특한 성질이 있다. 포도당은 모두 통과시키고 글루탐산을 주 에너지원으로 사용하는 것이다. 체내의 다른 세포는 포도당을 원하지만 뇌가 인슐린 신호를 보내주어야 혈관에 있는 포도당을 흡수하여 에너지원으로 쓸 수 있다. 포도당을 너무나 좋아하는 뇌가 자신이 먹을 것이 충분하다고 여길 때만 인슐린 신호를 보내 다른 세포도 먹을 수 있게 하는 것이다. 그런데 상피세포는 소장으로부터 포도당을 이미 흡수한 상태이다. 그런데 그것을 자신이 쓰지 않고 혈관으로 보내 뇌가 쓰도록 한다. 장세포도 생명활동을 위해서는 많은 ATP가 필요하고 ATP 합성을 위한 에너지원이 필요하다. 그 역할을 글루탐산이 하는 것이다. 국제 글루탐산 기술위원회(IGTC)가 동위원소를 이용해 실험한 결과 음식물로 섭취한 글루탐산은 95% 이상이 장내 에너지원으로 소비되는 것으로 밝혀졌다. 그리고 글루탐산은 세로토닌 양을 늘려 장운동을 활발하게 하고, 음식의 소화과정에서 체온을 높이는 역할을 하고, 글루타치온의 합성을 통해 항산화작용을 돕는 것으로 밝혀졌다. 글루탐산이 부족하면 장이 건강하기 힘들고 장이 건강하기 힘들면 몸 전체가 건강하기 힘들다. Ninety-five percent of the dietary glutamate is metabolized by intestinal cells in a first pass. Intestinal Glutamate Metabolism Peter J. Reeds3, Douglas G. Burrin, Barbara Stoll, and Farook Jahoor U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service, Children’s Nutrition Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX Although it is well known that the intestinal tract has a high metabolic rate, the substrates that are used to generate the necessary energy remain poorly established, especially in fed animals. Under fed conditions, the quantification of substrate used by the gut is complicated by the fact that potential oxidative precursors are supplied from both the diet and the arterial circulation. To circumvent this problem, and to approach the question of the compounds used to generate ATP in the gut, we combined measurements of portal nutrient balance with enteral and intravenous infusions of [U-13C]substrates. We studied rapidly growing piglets that were consuming diets based on whole-milk proteins. The results revealed that 95% of the dietary glutamate presented to the mucosa was metabolized in first pass and that of this, 50% was metabolized to CO2. Dietary glucose was oxidized to a very limited extent, and arterial glutamine supplied no >15% of the CO2 production by the portal-drained viscera. Glutamate was the single largest contributor to intestinal energy generation. The results also suggested that dietary glutamate appeared to be a specific precursor for the biosynthesis of glutathione, arginine and proline by the small intestinal mucosa. These studies imply that dietary glutamate has an important functional role in the gut. Furthermore, these functions are apparently different from those of arterial glutamine, the substrate that has received the most attention. SUMMARY The studies summarized above led to some general conclusions. First, under the conditions of our experiments, glutamate is the single most important oxidative substrate for the intestinal mucosa. Second, glutamate is clearly playing a quantitatively significant role in the biosynthesis of two conditionally essential amino acids (proline and arginine) and is a key factor responsible for protection of the mucosa (glutathione). However, the most important result to emerge from these tracer studies is that it is dietary glutamate that is important in these respects. This raises the intriguing questions whether dietary glutamate is an essential factor for the maintenance of mucosal health and whether some of the changes in intestinal mass and function that accompany parenteral nutrition represent the effects of a lack of enteral glutamate. There is some evidence in the literature to suggest that this might be so, and we are now starting to address this subject both in relation to the possible use of enteral glutamate supplements during parenteral nutrition and in relation to the functional consequences of the lack of enteral glutamate. 포도장은 소화 흡수된 후 상당량이 혈관을 통해 여러 세포에 전달된다  MSG는 뇌로 가기는 커녕 소장에서 대부분 소비되어 버린다   Is glutamine a unique fuel for small intestinal cells? - Alpers, David H. MD - Current Opinion in Gastroenterology: March 2000 - Volume 16 - Issue 2 - p 155 Although the small intestinal mucosa is designed to transport large quantities of all nutrients to the blood, the primary nutrients utilized by the enterocyte for growth and/or maintenance are quite restricted. The major fuels for the small intestinal mucosa are amino acids (glutamine, glutamate, aspartate), whereas glucose and fatty acids are of much less importance. Many of the experiments have been performed during growth or maintenance of mucosa in small rodents, especially the rat, a model in which the adaptation of the intestinal mucosa, at least to fasting, is quite different than in humans. A special role has been suggested for glutamine as a small intestinal fuel, compared with glutamate and aspartate, but the available data do not support this view. Clinical trials of glutamine supplementation suggest that, if glutamine has a role, it may be related to functions other than those relating to small intestinal function. 뇌에서 글루탐산 대사

|

||||

|

|

|||