두뇌 ≫ 구조, 구성 ≫ 기억술

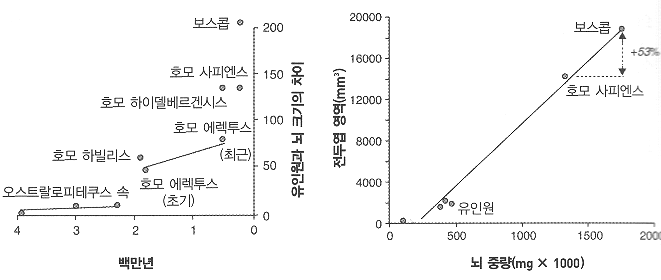

큰뇌 : Mormyrids , 보스콥인

두뇌의 발달과정

- 최초의 뇌, 큰 뇌

- 두뇌는 후각세포의 진화물 : 후각은 가장 원시적(원초적) 감각

- 신피질은 후각의 감각방식의 용량확대_빅브레인

- 뇌발달 요인 : 내장기관의 축소, 직립보행

- Pallium, 신경전달 방식의 변화

코끼리고기 : 전체 에너지의 60%를 뇌에 공급

또한 코끼리물고기는 복잡한 전기기관(electric organ)을 가지고 있었는데, 전기장(electric fields)을 발생시키는 이 기관을 사용하여 혼탁한 강바닥에서 먹이를 탐사하고 (이 과정은 전기정위(electrolocation, 전기를 감지하는 능력)로서 알려져 있다) 항해를 하는 데에 도움을 얻고 있었다.

’인간뇌 신피질의 팽창’ 일으킨 유전자 찾아

오철우 2015. 02. 27

독일 막스플랑크 분자세포생물학·유전학 연구소와 진화인류학연구소 등의 연구진은 최근 과학저널 <사이언스> 온라인판에 낸 논문에서 인간의 진화 과정에서 대뇌 신피질의 팽창을 일으키는 데 중요하게 작용한 유전자를 찾아냈다고 보고했다. <사이언스> 뉴스 보도를 보면, 연구진은 숨진 태아 조직과 쥐의 배아를 대상으로, 여러 실험 기법을 사용해 두 종 간에 뇌 조직 형성 초기의 유전자 발현 차이를 비교 분석했다. 이런 과정을 거쳐 연구진은 쥐에서는 나타나지 않지만 인간한테서 나타나는 유전자 58종을 추려냈으며, 이 가운데에서 뇌의 신피질을 만드는 신경 전구세포의 증식을 일으키는 유전자로서 ‘ARHGAP11B’를 찾아냈다

연구진은 이 유전자가 발생 단계의 쥐의 뇌에서 발현하도록 하는 실험을 수행했으며, 이 실험에서 인간 유전자 ‘ARHGAP11B’가 발현된 쥐의 뇌 신피질 부위가 일반 쥐보다 훨씬 더 크게 성장했으며 또한 인간 대뇌피질에 나타나는 독특한 특징인 신피질 주름(접힘)도 일부 생성된 것으로 확인했다고 보고했다.

이번 연구진에는 네안데르탈인, 데니소바인 같은 원시인류 유전체(게놈)를 현생 인류와 비교해 인류 진화를 연구해온 스반테 파보(Svante Paabo) 박사도 참여했다. 연구진은 인간 대뇌 신피질의 성장에 관여하는 ‘ARHGAP11B’ 유전자가 침팬지와 인간이 서로 갈라진 이후에 출현한 것으로 보인다고 밝혀, 이 유전자가 신피질의 팽창에서 중요한 구실을 했을 것으로 보았다.

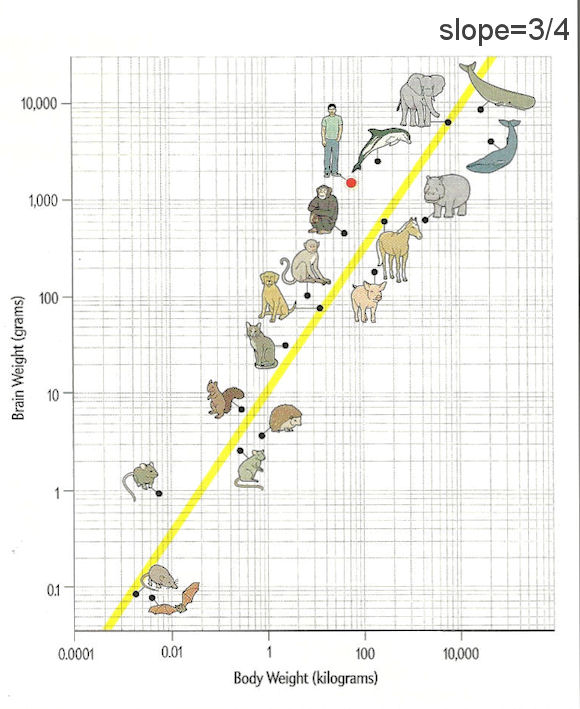

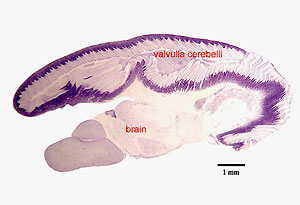

elephant-nose fishes

The African mormyrids or elephant-nose fishes were noted for having unusually large brains already more than a century ago (Erdl, 1846). For a mean body mass of 26 g, the mean brain weight of Gnathonemus petersii reaches 0.53 g, almost three times its expected mean value of 0.19 g, as calculated from the relationship between brain size and body size in teleost fish (Kaufman, 2003).

This character is probably, at least in part, related to their ability to sense prey and to communicate by generating and perceiving electric fields (Nieuwenhuys and Nicholson, 1969). In contrast with mammals, it is the cerebellum, and not the telencephalon that is greatly enlarged in these fishes. More precisely, the most enlarged part of the mormyrids cerebellum (or “gigantocerebellum”, Nieuwenhuys and Nicholson, 1969) is the valvulla cerebelli (fig. 2). This rostral protrusion of the cerebellum is only present in actinopterygian fish. In elephant-nose fishes, the valvula cerebelli covers most of the rest of the brain (fig. 2). In contrast, in another highly derived brain such as the human brain, it is the telencephalon, and more specifically the neocortex, a telencephalic structure unique to mammals, that entirely covers the rest of the brain (fig. 3).

Brains are always costly organs in terms of energy consumption. What are then the challenges faced by humans and mormyrids?

Vertebrates show remarkably constant ratios of brain to body O2 consumption, the brain using 2–8 % of resting body O2 consumption, suggesting that evolution has put limits on the energetic cost of brain functions (Mink et al., 1981). Only man is an exception to this rule. The adult human brain accounts for 2% of the total body mass but consumes some 20 % of the O2 taken up by the resting body. This represents an exceptionally high rate of energy use among vertebrates and appears to have remained undisputed.

The results of Nilsson (1996) however suggest that, in the electric fish Gnathonemus petersii, the brain is responsible for approximately 60% of body O2 consumption, a figure three times higher than that for any other vertebrate studied so far, including human.

The exceptionally high energetic cost of the Gnathonemus petersii brain appears to be a consequence both of the brain being very large and of the fish being ectothermic (Nilsson, 1996). At the same temperature and body size, total energy expenditures of ectothermic vertebrates are about 1/13 of those of endotherms but brain energy expenditures are quite similar. When considering the whole-body energy budget, it is thus comparatively more expensive for an ectothermic vertebrate to have a large brain. This may be a reason why most ectothermic vertebrates have relatively small brains.

Consequently, the fact that Gnathonemus petersii is an ectothermic vertebrate and has such a huge brain makes this organ an exceptionally expensive part of the whole body (Nilsson, 1996). To some extent, Gnathonemus petersii therefore faces an ecophysiological challenge unparalled in the animal kingdom, including human.

Differences in cognition and relative brain size are among the most striking differences between humans and their closest primate relatives. The Energy Trade-Off Hypothesis predicts that a major shift in energy allocation across tissues occurred during human origins in order to support the remarkable expansion of a metabolically expensive brain. Recent genetic studies, based on genome wide scans for signatures of adaptation and comparative brain transcriptomics, suggest a role for metabolic genes in human evolution consistent with the Energy Trade-Off Hypothesis. However, the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying this hypothesis remain unknown and experimental evidence is lacking. Despite the numerous advantages of studying great apes, including extensive genomic and medical data, there are ethical and practical limitations to performing controlled experiments. Fortunately, human is not the only species that has experienced increased brain size. For instance, it has been shown that the brain of the elephant-nose fish (Gnathonemus petersii) from the Mormyridae family is extremely enlarged and consumes proportionally three times more oxygen than the human brain. Because the Mormyrids also exhibit spectacular variation in brain size, they offer a unique opportunity to study the genetic bases of the Energy Trade-Off Hypothesis with laboratory tractable organisms. I will focus on two species with significant brain size differences: G. petersii and Brienomyrus brachyistius. Using a combination of comparative transcriptomics across multiple tissues and computational approaches, I will identify genes involved in a metabolic trade-off. Overlaid with previous genomic studies on primates, these results will contribute to a better understanding of human origins. This project is also a necessary first step to develop a genetic model for studying the Energy Trade-Off Hypothesis.