| Hint | Food | 맛과향 | Diet | Health | 불량지식 | 자연과학 | My Book | 유튜브 | Frims | 원 료 | 제 품 | Update | Site |

|

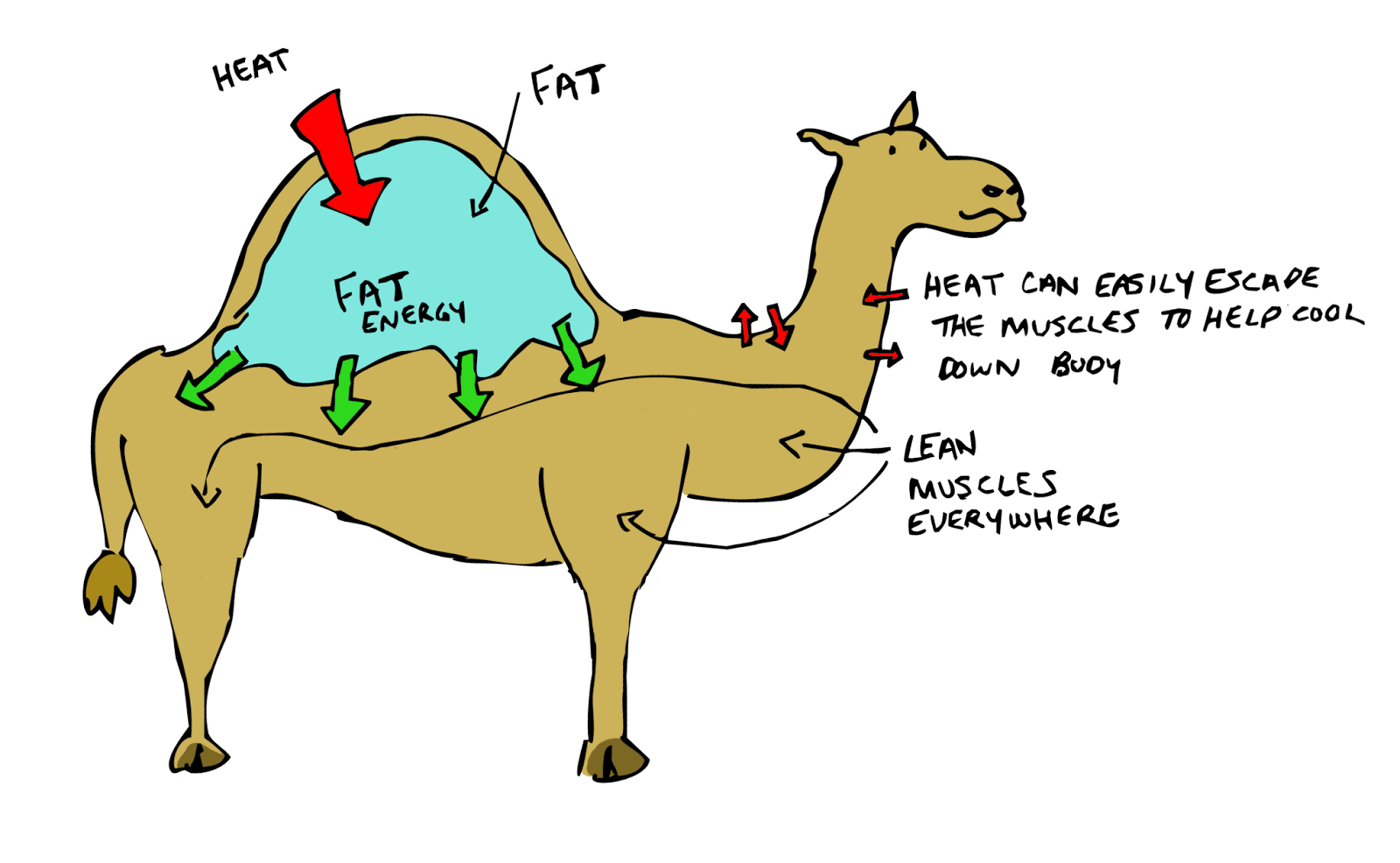

식품 ≫ 지방 ≫ 지방종류 낙타 : 지방 연소 지방의 역할 - 낙타는 40kg의 지방을 에너지와 물로 전환하여 생존한다 - 일부 철새들은 몸의 50%를 지방으로 채운 후 3000~4000km를 날아간다 - 동면 : 지방을 비축하여 물을 먹지 않고 겨울 잠을 잘 수 있다 - 낙타는 40kg의 지방을 에너지와 물로 전환하여 생존한다 위키 Ecological and behavioral adaptations Camels do not directly store water in their humps as was once commonly believed. The humps are actually reservoirs of fatty tissue: concentrating body fat in their humps minimizes the insulating effect fat would have if distributed over the rest of their bodies, helping camels survive in hot climates.[15][16] When this tissue is metabolized, it yields more than one gram of water for every gram of fat processed. This fat metabolization, while releasing energy, causes water to evaporate from the lungs during respiration (as oxygen is required for the metabolic process): overall, there is a net decrease in water.[17][18] Camels have a series of physiological adaptations that allow them to withstand long periods of time without any external source of water.[16] Unlike other mammals, their red blood cells are oval rather than circular in shape. This facilitates the flow of red blood cells during dehydration[20] and makes them better at withstanding high osmotic variation without rupturing when drinking large amounts of water: a 600 kg (1,300 lb) camel can drink 200 L (53 US gal) of water in three minutes.[21][22] Camels are able to withstand changes in body temperature and water consumption that would kill most other animals. Their temperature ranges from 34 °C (93 °F) at dawn and steadily increases to 40 °C (104 °F) by sunset, before they cool off at night again.[16] Maintaining the brain temperature within certain limits is critical for animals; to assist this, camels have a rete mirabile, a complex of arteries and veins lying very close to each other which utilizes countercurrent blood flow to cool blood flowing to the brain.[23] Camels rarely sweat, even when ambient temperatures reach 49 °C (120 °F).[7] Any sweat that does occur evaporates at the skin level rather than at the surface of their coat; the heat of vaporization therefore comes from body heat rather than ambient heat. Camels can withstand losing 25% of their body weight to sweating, whereas most other mammals can withstand only about 12–14% dehydration before cardiac failure results from circulatory disturbance.[22] When the camel exhales, water vapor becomes trapped in their nostrils and is reabsorbed into the body as a means to conserve water.[24] Camels eating green herbage can ingest sufficient moisture in milder conditions to maintain their bodies' hydrated state without the need for drinking.[25] Domesticated camel calves lying in sternal recumbency, a position that aids heat loss The camels' thick coats insulate them from the intense heat radiated from desert sand; a shorn camel must sweat 50% more to avoid overheating.[26] During the summer the coat becomes lighter in color, reflecting light as well as helping avoid sunburn.[22] The camel's long legs help by keeping its body farther from the ground, which can heat up to 70 °C (158 °F).[27][28] Dromedaries have a pad of thick tissue over the sternum called the pedestal. When the animal lies down in a sternal recumbent position, the pedestal raises the body from the hot surface and allows cooling air to pass under the body.[23] Camels' mouths have a thick leathery lining, allowing them to chew thorny desert plants. Long eyelashes and ear hairs, together with nostrils that can close, form a barrier against sand. If sand gets lodged in their eyes, they can dislodge it using their transparent third eyelid. The camels' gait and widened feet help them move without sinking into the sand.[27][29][30] The kidneys and intestines of a camel are very efficient at reabsorbing water. Camel urine comes out as a thick syrup, and camel feces are so dry that they do not require drying when the Bedouins use them to fuel fires.[31][32][33][34] Why Camels are Actually Amazing Devoting a whole article to one animals is a little out of character for Sketchy Science. With a few exceptions that were screaming out to be explained (the disgusting lives of sloths, the indestructible tardigrades) we tend to relegate interesting facts about well-known animals to the world of Sketchy Facts. The thing is, if we tried to do that with camels, our loyal readers would miss out on a more complete understanding of one of the most incredible animals on the planet. You often hear that a camel is just a horse designed by committee, meaning that the focus was on the details at the expense of the beauty and functionality of the overall animal. Despite the fact that no animal is designed at all, there are other reasons that this cliché is just dead wrong. All those details evolved over millions of years to make camels almost ridiculously well-suited to their environments (which, as we will see, vary insanely) and have left these creatures with a capacity to surprise that is beyond belief. If you think you know about camels, odds are you haven’t even scratched the surface (unless you are some sort of camel biologist). Even the things the average person thinks they know about camels are just plain wrong. For example, a camels hump doesn’t store water. If it did, humps would jiggle around like elevated waterbeds with every step the animal took. In reality, the camel’s most defining feature is a massive mound of fat that can weigh as much as 80 lbs (41 kg). Having all their body fat in one place means the rest of the camel’s body is super-efficient at shedding heat, a handy adaptation to desert life. Their humps also contribute to their ability to go weeks without a real meal. They can use their humps as fuel (which is all fat really is anyway) and the longer they go without food, the more shriveled their humps get.  So if their humps aren’t thirst quenching reservoirs, how do camels go so long without drinking anything? As it turns out, camels are not the arid-loving beings we all think they are. It is true that some camels can go months without drinking water, but how they do it has less to do with storage and more to do with economy. The camels that can go seemingly forever on grass alone are the ones that are adapted to the cold areas of the Mongolian steppe. Since mammals lose most of our moisture when our bodies overheat, cold weather is a great mechanism to holding in water. As a side note: scientists think that camels actually evolved in the Canadian arctic before migrating to Asia during the last ice age. Camels also have another wacky, water-saving adaptation that is far less obvious. If you looked at camel blood under a microscope and compared it to the blood of, say, a wombat or Bratt Pitt you would notice that the camels red blood cells look warped in the manner of a Salvador Dali painting. Camel’s red blood cells are oval (egg) shaped whereas most mammals have circular cells. The cool thing about oblong blood cells is that they can keep flowing easily, even when the liquid they flow through (plasma) starts to dry up. Their blood cells can also expand to 240% their normal size to hold water without bursting compared to 150% in most mammals. In the end, the blood cells do the trick that most people credit the humps with.  The other thing camels have going for them in terms of water conservation is that their body temperatures can vary wildly before their start to feel any stress. Humans start to feel sick if our core temperature fluctuates more than a few degrees, but camels are comfortable with an internal temperature anywhere from 33 to 40 degrees C (93 to 105 F). They accomplish this with another amazing adaptation: the ability to cool their brains independently from the rest of their bodies. Camels use their massive, cavernous nasal cavities to cool blood before it enters their brains, protecting neurons from heat damage. The veins in their heads are also located right up next to their arteries, allowing the oxygen depleted (and cooler) venous blood to absorb some of the heat from the arteries fueling the brain.  Finally, while we are hanging out in the camel’s head, there is one last crazy thing we should check out before calling it a day. If we manage to prop open the camel’s mouth without getting spit on (camel spit is actually a mix of their stomach contents and saliva, used to ward of predators) most of us will probably recoil in fear at the sight of what appear to be inch long fleshy spiked sticking out of the animal’s cheeks. The inside of a camel’s mouth looks like some kind of alien bear-trap, but those spikes are just another awesome adaptation. The “papillai” as they are called are just grotesquely enlarged versions of the same structures that human taste buds grow on. For camels, they help direct chewy food items like sticks and leaves to the stomach while protecting the cheeks and throat from damage. When you live in the desert you have to take whatever food you can get.  Hopefully you found this tangent-filled exploration of one of nature’s most amazing animals interesting and ideally you will remember all the incredible things about these misunderstood animals next time you are tempted to use a judgey cliché. Lest ye get spit on. |

||||

|

|

|||